Common Shoulder Syndromes

Stabilization Solutions for Common Shoulder Syndromes

Shoulder problems are rampant in modern society and are a common complaint of clients I see regular. While shoulder impingement, rotator cuff syndrome, and tendonitis are common clinical diagnoses, most shoulder problems share a common etiology: poor scapulothoracic stabilization. Common treatments — including joint and soft tissue manipulation, stretching, medications, heat, and electrical muscle stimulation — rarely succeed in providing significant long-term benefits because they don’t address the underlying stability issues of the shoulder complex. Although it is rarely discussed when dealing with shoulder issues, the cervical spine is a large contributor to scapulothoracic instability.

This article will discuss the relevant anatomy as well as the relationship of the cervical spine to shoulder instability and identify some of the commonly overlooked signs of both cervical and scapulothoracic instability. Additionally, this article will define a corrective and progressive exercise strategy based upon the principles of the Integrated Movement System™ (IMS)

Cervical and Scapulothoracic Dysfunction

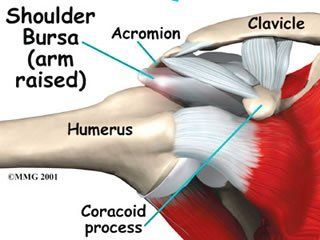

The first step in gaining confidence when working with shoulder problems is to develop an understanding of the anatomy and kinesiology of the cervical and scapulothoracic regions. While they are not often discussed together, the cervical spine and shoulder complex are intimately related. The cervical spine is composed of seven vertebrae that blend into the thoracic region of the spine. It functions as a base for the head as well as an important attachment point for several of the muscles that support the scapulothoracic region. Several muscles of scapulothoracic complex, including the levator scapula, rhomboid minor, and fibers of the upper and middle trapezius each have attachments on both the cervical spine and scapula.

The C5-T1 cervical nerve roots form the brachial plexus as they exit the foramina. The brachial plexus exits the neck between the anterior and middle scalene, travels underneath both the clavicle and the pectoralis minor prior to innervating the structures of the shoulder and upper extremity.

These relationships are important to understand, since dysfunctions in both postural support or proper movement patterns can have significant impact on the function of the shoulder complex. For example, disc herniations are a common cause of neck pain and dysfunction. Radicular symptoms such as numbness and tingling are usual symptoms of disc problems, but several other patterns often precede these symptoms. Decreases in internal shoulder range of motion and chronic trigger points in the levator scapula and rhomboid minor are two common early signs of irritation of the cervical nerve roots. While clients can experience problems at any disc level, C5-6 is the most common level for cervical disc bulges and herniations. Not so ironically, the nerve roots C5, 6, and 7 innervate the serratus anterior and disc irritations of the C5-6 level can be a cause of serratus anterior weakness and subsequent instability or winging of the scapulothoracic region.

This cervical instability must be improved when dealing with scapulothoracic dysfunction or there will be no long-term solution to these movement dysfunctions. While there are several causes of cervical instability, two of the more common ones include the forward head syndrome and downward scapular rotation syndrome. Their relation to scapulothoracic instability will be discussed below.

Forward Head Syndrome

Downward Rotation Scapular Syndrome

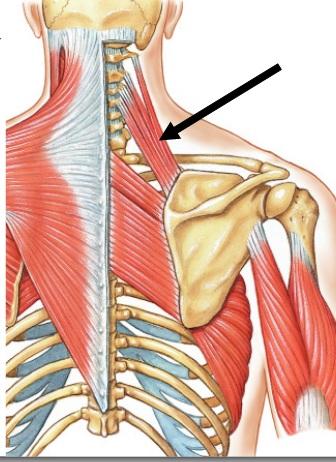

The “levator scapula sign” occurs when the scapula is insufficiently stabilized along its inferior border by the inferior fibers of the serratus anterior and lower trapezius. As the athlete performs a pushing or pulling pattern, rather than remaining stabilized, the superior angle of the scapula moves superior and medial on the thorax, and there is prominence of the levator scapula along the lateral aspect of the neck (see Figure 2). In addition to prominence of the levator scapula, hypertonicity can be palpated within the levator scapula as the athlete performs her patterns. Over-activation of the levator scapula also contributes to hyperextension of the mid-cervical spine as the levator scapula also functions as an extensor of the neck. This is a dysfunctional pattern that encourages downward rotation of the scapula especially when there is subsequent over use of the pectoralis minor as a primary respiratory muscle.

When there is over-activation of the downward rotators of the scapula (pectoralis minor, levator scapula, and rhomboids), it is common for athletes to struggle with scapular stabilization. This patterning can be viewed in several upper extremity patterns however is easiest to see as the athlete returns their arm from the overhead position (see Figure 3). Notice how the inferior angle of the scapula moves away from the thoracic cage as the arm is lowered — and this is without any weight in the arm. It is important to look and/or palpate for this instability as this dysfunction will only be exacerbated as the arm is loaded. Improved scapular stabilization must be achieved prior to progressing the athlete to the fundamental pushing and pulling patterns or the athlete will further ingrain these poor habits.These altered stabilization and movement patterns can lead to a host of additional shoulder and upper extremity conditions, including thoracic outlet syndrome, bicipital tendinopathies, and rotator cuff syndromes. Therefore, the corrective strategy for these conditions (as well as the forward head and downward rotation syndrome) is to improve respiration, stabilization, and integration of the fundamental movement patterns.

Integrating the Respiratory, Stabilization and Movement Systems

To specifically address the three most common causes of movement dysfunction — poor respiratory patterns, poor stabilization, and improper progressions of the fundamental patterns — the fitness professional must focus on improving the three principles of human function:

- respiration prior to stabilization

- stabilization prior to integration

- integration prior to progressions

RESPIRATION

Respiration must be optimized; otherwise, no other movement can be optimal. Proper diaphragmatic respiration must be established to ensure both optimal oxygenation as well as proper stabilization of the spine and thorax. In fact, faulty respiratory patterns have been linked to overall poor health in addition to poor stabilization of the trunk and spine. The diaphragm has been shown to have a role in both respiration and stabilization (Richards et al., 2004) and faulty patterning of the diaphragm has been indicated in dysfunctional stabilization of the trunk and spine (Hodges et al., 2001; Kolar, 2009).

STABILIZATION

Once optimal respiratory patterns and core activation have been established, the athlete can be progressed to restoring optimal scapular mechanics. Recall that stabilization of the scapula against the thorax and control of upward rotation must be established prior to loading the upper extremity. Research has demonstrated that the push-up plus (push-up with an additional protraction component) and dynamic hug (fly pattern performed with resistive tubing or cables) patterns are two exercises that effectively activate both the serratus anterior and subscapularis, two muscles that have been linked to shoulder instability (McClure, 2006). In reviewing the literature, it would be logical to include these two exercises in a corrective exercise routine for athletes with scapulothoracic or glenohumeral instability. However, when reviewing research it is important to understand EMG studies are limited in that an EMG only records muscle activity, not whether or not the muscle is actually being activated to perform optimally. This is where the athlete must be diligent in understanding both the research as well as the optimum functional kinesiology of a muscle prior to instituting a corrective exercise program.

There is no arguing the fact that the serratus anterior is heavily recruited during a push-up plus motion. In addition to its stabilization function, the serratus anterior functions as a strong protractor of the scapula. However, the serratus anterior must also adhere the scapula to the thorax cage and decelerate the humerus as the arm returns from overhead motion, two functions that are not guaranteed during the push up plus. Yes, it is maximally recruited during a push up plus, but does this prove that the scapula is under any better neuromuscular control than in other functional positions? Unfortunately, it does not. This is not to say that the push-up plus cannot be an effective exercise as part of a progressive rehabilitative program but rather point out its limitations if used early in the rehabilitative process.

Recall that most shoulder problems — as well as problems in the low back, neck, etc. — are not strength issues; they are motor control issues. Applying more strength will only benefit the athlete who has a defined weakness and who possesses optimal neuromotor programs. Adding strength does not ensure anything except that a athlete will get stronger. Adding strength to a client with poor neuromuscular patterns only ensures that the athlete will continue to compensate and use the same patterns they have habitually used.

The following series of exercises is key in establishing both optimal stabilization as well as movement awareness of the scapulothoracic and glenohumeral regions. Movement awareness is the most overlooked component to corrective exercise as the client must be made aware of how they are currently moving as well as what ideal patterns look and feel like. These patterns include the quadruped with arm reach, the wall plank with arm reach, and shoulder rotation patterns. It is important to remember that the goal of these patterns is to improve neuromuscular control of the scapulae and spine stabilizers, so it is important that the early phases of corrective exercise emphasize this point.

Wall Plank

The wall plank is an excellent pattern to establish both optimal scapular and spine alignment, as well as activation of the deep intrinsic stabilizers of both regions. In Figure 4, the athlete stands approximately one foot away from the wall and assumes an elbow plank position against the wall. Her upper arms are positioned level with the shoulders and she is cued into a neutral spine and scapular positions. These cues include:

- a long spine posture – the deep neck flexors are activated, the spine is in neutral posture;

- the scapula are positioned into upward rotation — the serratus anterior and lower trapezius are activated;

- the core is activated and the client maintains diaphragmatic respiration.

She slides one arm up the wall while stabilizing the opposite side and returns to the starting position. She repeats on the other side for the desired number of reps. It is important that the athlete controls the lowering of her arm (eccentric control) as she returns to the starting position. Equally important is that she maintains stability in the stationary arm, as the goal is to improve the stabilization function of the scapular stabilizers. Be sure to monitor for excessive levator scapula activity by observing the lateral aspect of the athlete’s neck.

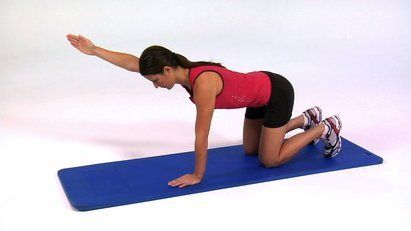

Quadruped with Arm Reach

As shown in Figure 5, the quadruped pattern begins with the athlete positioned in a quadruped posture with her elbows shoulder-width apart. She establishes neutral spine posture and the image of a long spine (as if someone is pulling her head by a string). She activates her serratus anterior and lower trapezius and maintains this activation throughout the pattern. She reaches one arm out as far as she can without losing scapular or spine position and returns to the starting position. She repeats on the other side, alternating each side until completed the desired number of reps. As with the wall plank, it is just as important to maintain stability in the stationary arm as the goal is to improve the isometric function of the scapular stabilizers. Be sure to monitor for excessive levator scapula activity by observing the lateral neck.

Reversed Rotator Cuff Patterns

The closed chain rotator cuff pattern is an excellent pattern to incorporate the scapular stabilizers as well as the muscles of the rotator cuff, specifically the subscapularis. Most rehabilitation exercises for the rotator cuff begin with fixation of the trunk and rotation of the humerus on the scapula, which is in direct contrast to the patterns that occur during development. As the child learns to crawl, he moves the scapula over a fixated humerus thereby developing optimal rotator cuff function. This concept will be used to incorporate rotator cuff function with scapulothoracic stability. Please note that because this is a higher-level pattern, it must only be performed by athletes that have established optimal stability of the cervical, scapulothoracic, and glenohumeral regions.

The athlete should begin by holding onto a barbell secured to a power rack before progressing to the TRX version — both are demonstrated below. The athlete begins with a very shallow angle of incline and then lowers his body as he develop stability and strength. The athlete grasps the bar or handles (see Figures 6 and 7) and stabilizes his scapula and spine. He reaches to the side with his free arm without losing the scapular control of the fixed arm or alignment of the spine. He rotates back to the starting position and repeats for the desired number of repetitions on each side. The rotation occurs around the glenohumeral joint making these patterns essentially a reversed rotator cuff exercise for the stationary arm.

Sets, Reps, and Tempo

Quality over quantity should always be

stressed whenever attempting to improve motor patterns. The first two patterns

— the wall plank-reach and the quadruped reach — are designed to improve

stabilization and motor control and are generally not taxing to the endocrine

or nervous systems. Therefore, these patterns need to be performed every day to

improve motor control as well as awareness and can be done so without much worry

of over-training. The athlete will perform these patterns 2 times per day for

5-10 reps per arm with a 2 second concentric and 2 second eccentric phase. This

is a great posture relief exercise for athletes who work long hours at a desk

or computer.

The reverse rotator cuff pattern is a higher level pattern and can easily lead

to an over-trained or fatigued rotator cuff. This pattern will be performed 2-3

times per week for 2-3 sets of 8-12 repetitions.

Integration

Once an athlete achieves optimal respiration and stabilization, they must be taught how to integrate these into the fundamental movement patterns including pushing and pulling patterns. During pushing and pulling patterns, the scapulae must remain stabilized on the thorax. As the arm is lowered from overhead, the scapula must be eccentrically controlled throughout the entire motion. This same eccentric control must be adhered to during the eccentric phase of the dumbbell or cable chest press.

Conclusion

The one thing that all upper extremity syndromes — including thoracic outlet, carpal tunnel, and rotator cuff — have in common: they are all a result of poor stabilization and/or movement patterns. Therefore, passive therapies, medications, or surgery are rarely a long-term solution because none of these options address the underlying stabilization or movement issues. To be a part of the long-term solution, fitness athletes must understand and be able to educate themselves about the proper methods of respiration, stabilization, and movement integration. This article described several common movement impairments that lead to scapulothoracic dysfunction and introduced the key components of integrating the respiratory, stabilization, and movement systems as a means of improving movement patterns. Hiring a sport therapist can greatly help improve and monitor these patterns, the sports therapist can become an important part of an athletes health care team and become part of the solution to the health care crisis.

References

Decker, D.J., Tokish, J.M., Ellis, H.B.,

Torry, M.R., Hawkins, R.J. (2003). Subscapularis Muscle Activity During

Selected Rehabilitation Exercises; The

America

Journal of Sports Medicine

;

31:126-134.

Hodges, P.W., Heijnen, I., Gandevia, S.C. (2001). Postural activity of the diaphragm is reduced in humans

when respiratory demand increases; Journal of Physiology

; 537(3):

999–1008.

Kolar, P., Holubcova, Z., Frank, C., Liebenson, C., Kobesova, A. (2009).

Exercise & the Athlete: Reflexive, Rudimentary & Fundamental Strategies.

International Society of Clinical Rehabilitation Specialists – course handouts,

Chicago, IL.

Kolar, P., Kobesova, A., Holubcova, Z. (2009). Dynamic Neuromuscular

Stabilization: A Developmental Kinesiology Approach. Rehabilitation Institute

of Chicago – course handouts, Chicago, IL.

Liebenson, C. (2007). Rehabilitation of the Spine: a Practitioner's Manual

.

2nd ed. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, PA.

McClure, P.W., Michener, L.A., Karduna, A.R. (2006). Shoulder Function and 3-Dimensional Scapular

Kinematics in People With and Without Shoulder Impingement Syndrome; Physical

Therapy;

86(8):1075-1090.

Osar, E. (2010). Assessing the Fundamentals-The Thoracic Connection- part 1.

PTontheNet. Retrieved from http://www.ptonthenet.com/articles/assessing-the-fundamentals-the-thoracic-connection-part-1-3286.

Osar, E. (2010). Assessing the Fundamentals-The Thoracic Connection- part 2. PTontheNet.

Retrieved from http://www.ptonthenet.com/articles/assessing-the-fundamentals-the-thoracic-connection-part-2-3302

, June

9, 2010.

Osar, E. (2007). Improving Shoulder Function-Part 1. PTontheNet. Retrieved

from http://www.ptonthenet.com/articles/Improving-Shoulder-Function---Part-1-2965.

Osar, E. (2008). Improving Shoulder Function-Part 2. PTontheNet. Retrieved

from http://www.ptonthenet.com/articles/Improving-Shoulder-Function---Part-2-3046.

Osar, E. (2008). Improving Shoulder Function-Part 3. PTontheNET. Retrieved from http://www.ptonthenet.com/articles/Improving-Shoulder-Function---Part-3-3066.

Richardson, C., Hides, J., Hodges, P.W. (2004). Therapeutic Exercise for

Lumbopelvic Stabilization: a Motor Control Approach for the Treatment and

Prevention of Low Back Pain. 2nd Ed

. u.a.: Churchill Livingstone,

Edinburgh.

Sahrmann, S. (2002). Diagnosis and Treatment of Movement Impairment

Syndromes.

Mosby, St. Louis, MO.

Article taken from PTontheNet and adapted by Apache Brave Sports Therapies

Richard Watson

Sports Therapist